Dim Bulbs Seek Truth, Results Uncertain

Everyone enjoys a hearty laugh at the expense of the online research-challenged. Â That was the stunning outcome, when one “Miss Kitty” meandered into a discussion of Owen Lattimore, armed only with what she thinks she recalls from Conservapedia and Wikipedia.

Here’s the fast facts, insofar as Kit remembers:

“While reading “Blacklisted by History,†I looked up a commie named Owen Lattimore (he’s the second one from the left, standing next to Mao Say Dung), who, while touring a Soviet death and concentration camp, callously brushed off the pleas of a desperate female prisoner to help her. He was well protected by the verifiably corrupt (by verifiably, I mean there were FBI tape recordings of tapped phone conversations discovered decades later to prove it), Truman Justice Department. There is a huge difference in the way Wikipedia portrays him and the way Conservapedia portrays him, with the writers at Conservapedia using Owen Lattimore’s own writings and other eye-witness accounts of the man’s actions to incriminate him. So the next time you want to look something up, check Conservapedia and you’ll see a big difference. Of course, the chorus of the voices on the right will say they are biased.“

I think the voices in Miss Kitty’s head are a chorus of voices on the left, and she’s channeling details of the Amerasia case not Lattimore’s, but we must hurry along.

The photo referred to  actually has Lattimore standing next to Peoples Liberation Army Commander Chu Te.

actually has Lattimore standing next to Peoples Liberation Army Commander Chu Te.

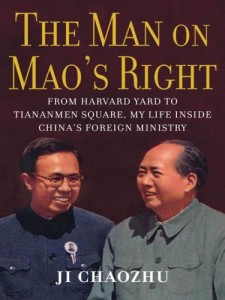

Lattimore was photographed with Mao, but it looks more like this:

Cause they all look alike?

Miss Kitty’s strenuous truth-seeking doesn’t extend to actually linking to either Conservapedia or Wikipedia‘s Lattimore entries, perhaps because they might dim the lustre of her story.

They each, in their own way, are more aligned with Miss Kitty then the truth.

Conservapedia refers to claims by the now dead Marvin Liebman of a conversation with former Gulag prisoner Elinor Lipper, who mentions the Henry Wallace Siberia visit in her memoir. Â

In Liebman’s version, Lipper told him Wallace’s sinister translator [Lattimore] steered the Vice President away from a woman prisoner screaming her innocence.

Several problems.

1. Lipper’s original book had no mention of Lattimore, references to him being added for the American edition after McCarthy surfaced his name. Â And none refer to the incident Liebman claimed to have heard. Lipper presented all her stories as second hand.

2. By all accounts, the Wallace party saw a Potemkin village, with KGB guards pretending to by miners for the day. Lipper even claims watchtowers were removed for the occasion. Why would the Soviets spoil the show with actual prisoners?

3. Lattimore spoke some Russian, but he wasn’t Wallace’s translator for the Soviet portion of the trip. Â He was along for later Mongol and Chinese conversations.

Conservapedia recalls the glory days of bipartisanship with a reference to a Lattimore slam “After the fall of China to the Communists in 1949, [by] then-Senator John F. Kennedy.” Â Â But Kennedy wasn’t elected to the Senate until 1952, and he got in this early attack on Lattimore before the fall of Chiang, in early 1949. Â But other than that, right on the money.

Conservapedia goes all in for the reference notes, referencing the maximum program anti-Lattimore pamphlet, “Communism at Pearl Harbor,” in which Lattimore basically caused World War II.

Conservapedia claims “When Lattimore resigned as editor of Pacific Affairs, he was succeeded by Michael Greenberg, a Communist Party member. Lattimore then became a member of the editorial board of the notorious Amerasia magazine.” Â Lattimore resigned board membership at Amerasia before leaving Pacific Affairs.

Kitty’s far too hard on Wikipedia, which smuggles in it’s own nut-ball references on Lattimore.

Wikipedia repeats unchallenged the tales of Alexander Barmin, who years after writing his post-Soviet memoir and talking to the FBI, suddenly recalled Lattimore’s participation in a preposterous Soviet scheme to smuggle arms into China. Â To a province they already occupied.

Wikipedia goes on about the FBI’s early and lengthy interest in Lattimore, without being too fussy about what those interests were.

On page 101 in part two of Lattimore’s FBI file, we learn that among other things they  tracked Mrs. Lattimore’s activities under their monitoring of “Foreign Inspired Agitation Among American Negroes.” The Bureau was concerned about the “Baltimore Committee for Home-Front Democracy,” which it reported “recommended equal opportunity to shop at any Baltimore store without discrimination because of race or color.”

Â Matusow: The Later Years

Matusow: The Later Years

Orlov spent the years of collectivization, Alliluyeva’s death and Stalin’s murder of most of the party leadership working abroad for Soviet intelligence in Berlin, the US, Vienna, London, and Copenhagen. He ended as intelligence chief in Madrid during the Spanish Civil War, where while apparently brooding over Alliluyeva’s suicide four years previously turned grief into strength hunting down Spanish Trotskyists and shipping Spain’s gold reserves to Moscow.  He didn’t break with the Soviets until 1938, and didn’t surface his tales of the Kremlin until the US anti-communist market appeared in the fifties.

Orlov spent the years of collectivization, Alliluyeva’s death and Stalin’s murder of most of the party leadership working abroad for Soviet intelligence in Berlin, the US, Vienna, London, and Copenhagen. He ended as intelligence chief in Madrid during the Spanish Civil War, where while apparently brooding over Alliluyeva’s suicide four years previously turned grief into strength hunting down Spanish Trotskyists and shipping Spain’s gold reserves to Moscow.  He didn’t break with the Soviets until 1938, and didn’t surface his tales of the Kremlin until the US anti-communist market appeared in the fifties. Barmine

Barmine  Serge spent the late twenties and the thirties hounded as a dissident, in the Gulag and then in exile, and is fairly reliable on other matters. He

Serge spent the late twenties and the thirties hounded as a dissident, in the Gulag and then in exile, and is fairly reliable on other matters. He  Kravchenko was a minor official who defected in the mid 40s while in New York for a wartime Soviet purchasing commission.

Kravchenko was a minor official who defected in the mid 40s while in New York for a wartime Soviet purchasing commission.

Harvey was gunning for the big leagues, and Red subversion of innocent youth was to be his ticket out of there. Â Shortly after this out of town production he came to Washington,

Harvey was gunning for the big leagues, and Red subversion of innocent youth was to be his ticket out of there. Â Shortly after this out of town production he came to Washington,

actually has Lattimore standing next to Peoples Liberation Army Commander Chu Te.

actually has Lattimore standing next to Peoples Liberation Army Commander Chu Te.